machine learning

Last tended to on May 15, 2022

Supervised learning is an example of observational inference – we’re just looking for associations between variables

I feel like this thread captures a really interesting divide / contrast of philosophies in machine learning research:

Researchers in speech recognition, computer vision, and natural language processing in the 2000s were obsessed with accurate representations of uncertainty.

— Yann LeCun (@ylecun) May 14, 2022

1/N

My goal now is to deeply understand the issues at hand in this thread. I found his mention of factor graphs in the shift to reasoning and planning AI was thought-provoking. I feel that causality and factor graphs and Bayesian and all that are very important. I just don’t know quite enough to put the pieces together yet.

Links to “machine learning”

artificial intelligence

Just gonna link this to machine learning for now.

ablation studies

Ablation studies are effectively using interventions (removing parts of your system) to reveal the underlying causal structure of your system. Francois Chollet (creator of Keras) writes about this being useful in a machine learning context:

Ablation studies are crucial for deep learning research -- can't stress this enough.

— François Chollet (@fchollet) June 29, 2018

Understanding causality in your system is the most straightforward way to generate reliable knowledge (the goal of any research). And ablation is a very low-effort way to look into causality.

Machine Learning Interviews Book

https://huyenchip.com/ml-interviews-book/

This is a book that provides a comprehensive overview of machine learning interview process, including the various machine learning roles, interview pipeline, and practice interview questions.

Below are my (WIP) answers to some of the questions in the book. DISCLAIMER: While these answers are accurate to the best of my knowledge, I can’t guarantee their correctness.

Machine Learning Interviews Book (Math > Algebra and (little) calculus > Vectors)

- Dot product

[E] What’s the geometric interpretation of the dot product of two vectors?

The dot product

- [E] Given a vector

This would simply be the unit vector in the direction of

- Outer product

[E] Given two vectors

We could also calculate this using numpy, like so:

import numpy as np a = np.array([3,2,1]) b = np.array([-1,0,1]) print(np.outer(a, b))

[[-3 0 3] [-2 0 2] [-1 0 1]]

[M] Give an example of how the outer product can be useful in ML.

Potentially…in some sort of collaborative filtering system, you’d want an outer product between

Many applications seem to use the Kronecker product (generalization of the outer product to tensors) – don’t quite understand them yet, but here are a few:

- Optimizing Neural Networks with Kronecker-factored Approximate Curvature

- Beyond Fully-Connected Layers with Quaternions: Parameterization of Hypercomplex Multiplications with 1/n Parameters

There has to be something simpler that I’m missing.

- Optimizing Neural Networks with Kronecker-factored Approximate Curvature

[E] What does it mean for two vectors to be linearly independent?

A set of vectors is linearly independent if there is no way to nontrivially combine them into the zero vector. What this means is that there should e no way for the vectors to “cancel each other out,” so to speak; there are no “redundant” vectors.

For only two vectors, this occurs iff (1) neither of them is the zero vector (otherwise the other vector could easily be canceled out by a scalar multiple of

- [M] Given two sets of vectors

and

I think more precisely we’d want to determine whether the vector spaces spanned by - Given

Not enough information. For example, let - Norms and metrics

[E] What’s a norm? What is

Can be thought of as a vector’s distance from the origin. This becomes relevant in machine learning, when we want to objectively measure and minimize a scalar distance between the ground truth labels and model predictions.

So first, we get the vector distance between the ground truth and prediction, which we can call

…and so on.

I can’t find anything on

- [M] How do norm and metric differ? Given a norm, make a metric. Given a metric, can we make a norm?

My understanding is that a norm is simply a mathematical operation on a vector, whereas a (loss) metric is measuring the distance between two things. Given a norm, let’s take the

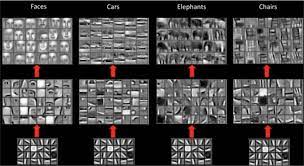

composability (A machine learning example of compositionality)

is that a computer vision model’s early layers will implement an edge detector, curve detector, etc., which are modular pieces that are then combined in various ways by higher-level layers to form dog detectors, car detectors, etc.

But ultimately the ways in which machine learning models, at the moment, can “intelligently” combine different pieces and parts is limited. See the tweet about DALL-E trying to stack blocks, bless its heart:

The ways in which #dalle is so incredible (and it is) really put a fine point on the ways in which compositionality is so hard pic.twitter.com/I6DC4g53MK

— David Madras (@david_madras) April 8, 2022

One step towards compositionality is the idea of neuro-symbolic models. Combining logic-based systems with connectionist methods.